I Am Gay and Want My Man Friend Feed Me Scat

Santiago, Chile resident Daniel Zamudio died on March 27th, of injuries sustained from a torturous, hours-long homophobic attack perpetrated against him by neo-nazis. He was 24 years old.

TWENTY FIVE days ago, a semi-conscious young man was found in the park where I rollerblade most Tuesdays in Santiago, Chile.

He had been tortured, mutilated, scarred, and broken. He was in a coma for three weeks, and his prognosis was never good. Discussions about whether or not he was actually brain dead filled the newspapers. He finally died, and I feel a wave of relief for his parents, coupled with great sadness for anyone who is gay or knows anyone gay. That is to say, all of us.

Here in Santiago, people had repeated the details of the attack to one another, the swastikas carved into Mr. Zaumdio's flesh, the large rock the assailants dropped on him time and time again. We don't have an anti-discrimination law in Chile, and people keep on asking each other if this will galvanize legislation, like the death of Matthew Sheppard did in the United States in 2009.

I don't know the answer to that, and I don't think any of us do. Movilh, (El Movimiento de Integración y Liberación Homosexual, a gay rights organization) put the following on their website today:

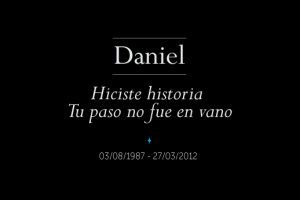

Daniel: You made history. Your passing was not in vain. Screenshot Movilh website.

Systemic injustice

On the judicial side of discrimination, a decision was recently handed down by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), slapping the Chilean government with an $80,000 fine for violating a woman's right to a private life in a custody dispute involving her three minor children.

The case was in the news when I first got to Chile, and in May of 2004, the Chilean Supreme Court ruled against Karen Atala, the "lesbian judge" who was fighting for custody from her husband from whom she was separated. The law in Chile — in all its chauvinist glory — a priori awards custody to mothers, barring unusual circumstances.

The Chilean court had ruled against Ms. Atala receiving custody due not to the fact that she was gay, but to the fact that she shared her life with a same-sex partner. On the basis of her cohabiting with her partner, Karen Atala's children were (over their own objections) placed with their father, from whom Ms. Atala had separated some time before.

Courts in Chile went over and over the decision, and the case was finally heard by the IACHR, and a decision handed down at the end of February indicating that the Chilean courts had acted in a discriminatory manner with regards to the girls' custody, and reiterated that "a person's sexual orientation is completely irrelevant for determining the fitness of a parent for retaining custody of their children."

In addition to the wrist-slapping decision with its $80,000 fine, the Commission requires that Chile "adopt measures to prevent the repetition of these violations, including legislation, public policies, programs, and initiatives to prohibit and eradicate discrimination based on sexual orientation in all areas of the exercise of public power, including the administration of justice."

Last night I had a conversation with some Chileans I don't know very well, and when I brought up the Atala case, they said, "but that's old news, it was years ago." I don't know how to make people see the connection between legally sanctioned anti-gay discrimination at the judicial level and a family who has to bury their son after 24 days of watching him suffer.

The president of Movilh, Rolando Jiménez, has asked that the non-discrimination law currently under discussion in Chile bear Mr. Zamudio's name, as reported in the national newspaper La Nación. He says Mr. Zamudio has become a "symbol of what we don't want in Chile."

I hope that what Movilh has posted on their website and what people ask about future legislation is true, that this man's passing was not in vain.

schneidermobleclat.blogspot.com

Source: https://matadornetwork.com/change/gay-mans-death-to-lead-to-anti-discrimination-laws-in-chile/

0 Response to "I Am Gay and Want My Man Friend Feed Me Scat"

Post a Comment